The Endangered Archives Programme

Major Research Project Award 2012-2013

EAP 608: Guinea's Syliphone archives II

A personal account

EAP 327: "Guinea's Syliphone archives" (2009).

and the complete catalogue of recordings.

All of the archival project material is freely available to the public online via the British Library Sounds website. Please note, however, that in October 2023 the British Library experienced a significant cyber-attack, and the collection is currently unavailable. The British Library have indicated to me that they hope to have the collection again available to the public in late 2025. I will update this web page accordingly...

In 2008, funded by the Endangered Archives Programme, I commenced the digitisation, preservation and archiving of Guinea's national sound archives, located in the Radio Télévision Guinée (RTG) buildings in the inner city suburb of Boulbinet, Conakry. I had limited time to complete the work, and in 2009 I received further funding to deliver this large project, which I estimated to contain in excess of 5,000 songs on 1/4" reel-to-reel format.

Due to Guinea's volatile security situation in 2009, however,

I

was forced to end the project

early. I had hoped to return to Guinea in 2011, however my

archival partner, the Ministry of Culture, was one of the

last ministries to be named by Guinea's new civilian government.

There was thus

no Minister to

approve my project by the deadline

of the funding application.

I therefore re-applied for funding in 2012

and arrived in August of that year, with six months

of funding to complete the project.

Upon arrival, three years' absence from Conakry felt more like three weeks! The city had changed little, though the rickety dwellings and shops on the main route out of town had steadily been demolished to make way for shiny new apartment projects. The "ambiance" of the city, which was most foreboding in 2009 when the capital and the nation were on a precipice, bore much less tension. Guinean soldiers still strutted the streets, as they have done for decades, though were now without their machine guns tossed over their shoulders. Guinea's new President, Alpha Condé, had decreed that such arms must remain in their barracks.

Delays in trying to commence the archival work at the RTG, however, remained as a constant. Though I attended the offices of the Ministry of Communication and the RTG every day for a month, and presented my credentials and documents as verified and supported by former government Ministers, the responses - especially from the RTG - was both familiar and vague: "Ah, but things have changed…”. The previous government's approval for my project was dismissed as irrelevant and was thus rendered into limbo, and it became increasingly clear that, as per my previous projects, senior RTG staff were disinterested in achieving the goal of preserving and digitising the sound archive unless, I reckoned, it of was of direct benefit to them. Their position was most frustrating, given their role to preserve Guinean arts and culture. Their recalcitrance is well-known in Guinea, especially amongst its musicians.

It was

therefore a

surprising and

reassuring turn of events when

the Minister of Communication (who had

oversight of the RTG), his Chef de Cabinet and his Secretary

General were all dismissed by the President, for failures

elsewhere. Unlike his predecessors, the incumbent Minister,

Togba Kpoghomou, approved the sound archive project

without ado. Given my previous experiences trying to

complete the sound archiving of the RTG

in 2008 and 2009 (see the links

above), I worked like a man possessed

for over 100 consecutive days to archive, preserve and digitise

the reel-to-reel audio tapes. Those days,

productive as they were, were amongst the most fulfilling

of my life. Through sicknesses,

broken ribs and all manner of

distractions, nothing deterred me. Particularly

not the RTG senior staff's continued

indifference towards the sound archival project

(even though their Minster had approved it), nor their recalcitrance

and nor their dismissive attitudes to me and my staff. Nothing. I was on a

mission, and determined to complete it.

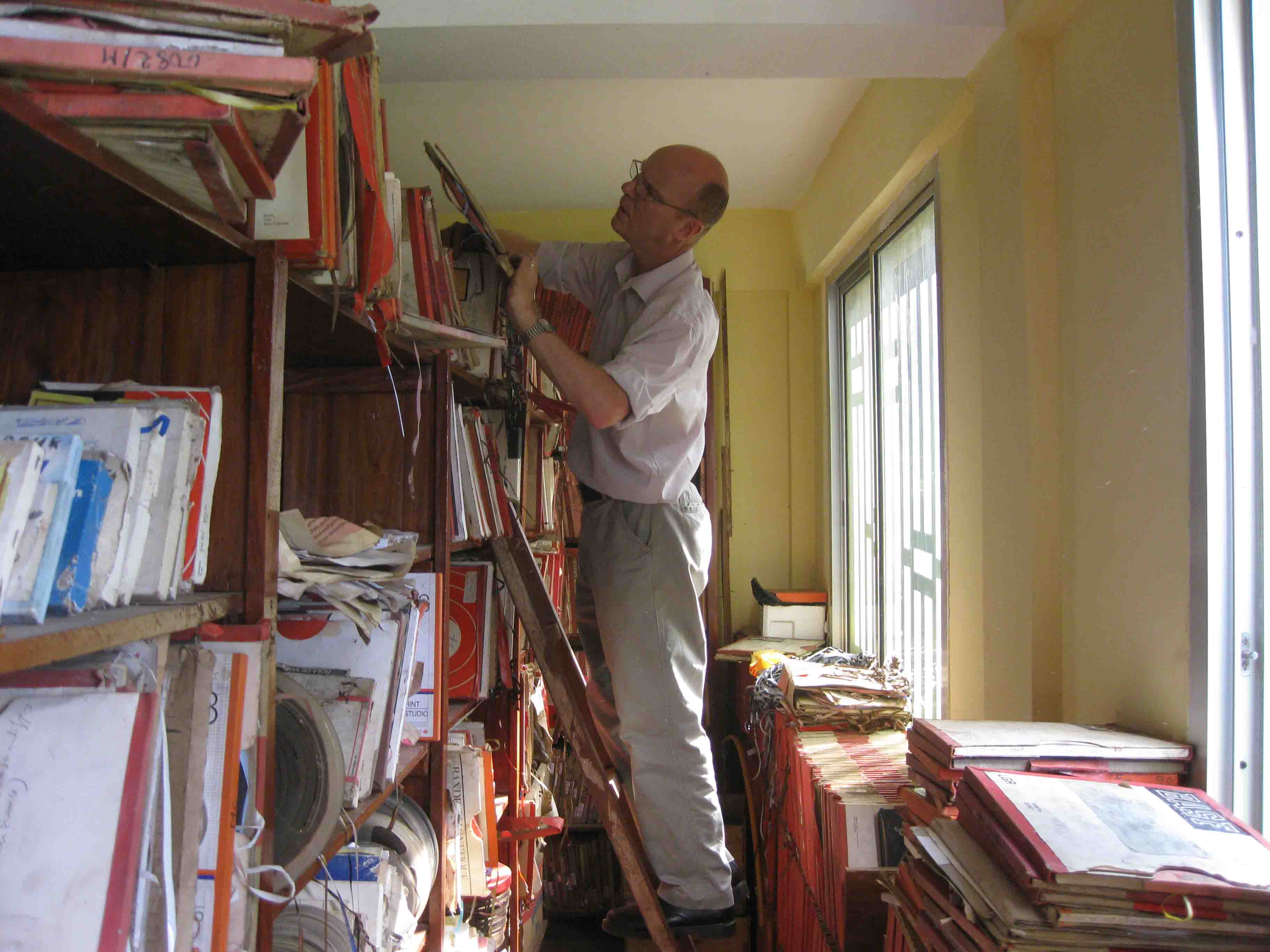

The RTG offices in Boulbinet, Conakry

At work in the archive

The archival

work thus commenced in

earnest in early September 2012. On one day, I archived

28 audio reels of 1/4" magnetic tape! Huge! On other days

I could only archive just 4 or 5 reels.

The work varied according to the size of the

audio reels and their states of

disrepair. I recall preserving an early 1960s recording of the

Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine, all tracks unreleased on

vinyl, where the tape was so brittle that

it would snap every few seconds during play.

The tape consisted of five 3 minute

songs and it took nearly a day to

splice, and re-splice, until it was playable.

During the earlier 2008 and 2009 RTG sound archival projects, I had prioritised the archiving of Guinea's orchestras, reasoning that these were the most significant. What remained to be archived in the collection, I surmised, were largely the recordings of “folklorique” music by Guinea's ensembles and soloists. Though I was familiar with this music to an extent, for example as performed by Malinké griots and Fulbé ensembles, as the archival work progressed I began working with Guinean musical heritages that were entirely unfamiliar, for example the music of the Kissi, Toma and Baga ethnic groups. It was a revelation to hear this music and the unreleased recordings by notable Guinean musicians such as Farba Tela, Ilou Dyohèrè, Binta Laaly Sow, Binta Laaly Saran, Sory Lariya Bah, Jeanne Macauley, and the group Koubia Jazz. These artists, unfortunately, are largely unknown outside of the West African diaspora, for the RTG archive (as an extension of the Guinean government) owned the rights to the recordings, and upon the death of President Sékou Touré, broadcasts of their music was very limited indeed. Following the death of President Touré in 1984, little of the RTG archive was broadcast to the public on the national radio, as much of it was deemed politically sensitive. To the new regimes that followed, the music of the Touré era served as a stark reminder of an an earlier period in Guinea's history, when a “cultural renaissance" and its corresponding "cultural revolution" were implemented by Sékou Touré under the banner of "authenticité", and which flourished. The sound archive had the potential, through its music, to remind Guineans of an era when an their nation proclaimed its independence and celebrated its diversity and its politics, music and arts, the latter through significant government sponsorship. "Archives are sites of power..." is a statement that applies most readily to this context. What really irked me, though, was that a generation of young Guineans had grown up in the in 1990s and 2000s without knowing the music that their mothers and fathers had not only created but enjoyed listening to. And what great music it was, with just a portion of it released to international audiences on vinyl records via the Guinean government's Syliphone recording label.

What was most surprising to me, however, was the extent of Fulbé in in the sound archive.

I have

published many articles on the politics

of Sékou Touré,

whose endeavours to instil his vision of the Guinean

nation is clearly evidenced in his cultural policy,

known as authenticité. To provide a brief overview, one of

the key aspects of authenticité was realised through government

funding of orchestras and ensembles in each of Guinea's 35 regions, so as to

give a broad and equal representation to all of the nation's language groups and

cultures. With respect to the music of the Fulbé, however, a language group who

represent 40% of Guinea's population, only 3% Syliphone recordings were

performed in Fulfuldé, the language of the Fulbé. Surely this is not an accurate

reflection of Guinea’s cultural policy, which proclaimed to represent “the music

of the nation”! As I suggest

in my publications, the cause of this marginalisation of

Fulbé music resides in the decades long power struggle in Guinea between

the Fulbé and the Malinké. Prior to independence in 1958, Guinea's Fulbé

population represented a voting bloc who had opposed Sékou Touré and his

political party, the PDG. From the early 1960s, a struggle

unfolded agaagainst the increasingly autocratic President and

the PDG, whereby multiple conspiracies and attempted coups we were

proclaime and thwarted. Touré regularly singled out the Fulbé as being behind these

"plots", and Fulbé politicians, traders, merchants and citizens were

subsequently targeted and imprisoned. The intimidation of any domestic

opposition to government rule, coupled with the

increasingly dire economic restraints, resulted in

over 1,000,000 Guineans fleeing to neighbouring countries or abroad:

some 20% of the population, many of

whom were of Fulbé ethnicity. The 3% of Syliphone

songs which are performed in Fulfuldé reflects not the harmonious nation under

the guise of an "authentic" cultural policy, but that of a marginalisation of

the Fulbé voice... Yet, here in the RTG archive, were

hundreds of reels by the nation’s best Fulbé musicians, most of which had never

been heard outside of Guinea.

On occasion, I would come across reels of music which had "n "not for broadcasting" written on the cover. An example of this is below (note "A ne pas diffuser", near the bottom, a "Folklore Pular", or "Fulbé folkore" musical recording). During the Sékou Touré years (1958-1984), the government employed numerous censors who approved music held in the RTG archives prior to broadcast. The RTG was the only radio station in Guinea for close to 40 years, and its large transmitter broadcast throughout the nation and to neighbouring states.

With November 2012 approaching, I had nearly completed the archiving of the 1/4" tapes, thus the end of the archival project was in sight. Given this, I enquired about the existence of an additional sound archive that I had been shown, just once, briefly, in 2009. It was a room adjoined to the RTG building complex close to the local Guinean army barracks. Upon enquiry, the senior RTG staff informed me that this archival room "no longer existed". Quite odd, as it clearly existed: one could see it! Upon further enquiry, RTG management’s response changed: "The archive does in fact exist, but it doesn't contain any music, just speeches by Sékou Touré and recordings of PDG conferences". With time, and upon further enquiry, this also changed to: "There was music in the archive, but not very much, and it contains only copies of music from the main archive".

Nearing the end of the project, however, the attitude of the senior RTG staff altered. Their earlier indifference and recalcitrance dissipated, coinciding, as it were, with the publicity that the archival project was increasingly attracting. To blunt their entrenched oppostion to the project, wherein they had not received any personal funds as part of the overall project budget (my reckoning), I had garnered the wide support of Guinean musicians, staff at the National Library (led by the wonderful Dr Baba Cheick Sylla, may he rest in peace), and former Ministers and public servants. I had also promoted the project on many of Conakry's public radio stations (where the DJs tried their best to test my knowledge by playing random songs!). Thus forearmed, I officially requested access to the "mysterious" second archive, which as it happened was widely known by all at the RTG (!) as "the annexe".

Granted access, upon entering the annexe I

was aghast to see perhaps 10,000 audio reels of 1/4" magnetic

tape, arranged in perfectly neat rows.

These, I was told, were recordings of Sékou Touré's

speeche and of PDG

conferences. In the corner of the annexe room, however, were

two long rows of reels of tapes, very poorly stored.

Many of them had no cover to protect them, and if they

possessed a cover nothing was written on them at all. Some of

the tapes, however, were clearly marked and

were of Guinean orchestras and ensembles. Many

others were

entangled in spaghetti-esque and serpentine entwinements. These

audio reels all required archiving, and I realised that I would

be in Guinea for a lot longer than I had planned...

I had

completed the archiving of all the audio reels in the RTG's

main archive, so comcommenced to

archive those in the "annexe". These annexe reels, as I soon

discovered, were predominantly of Fulbé music. It was very odd,

I thought, that so much Fulbé music existed in this

"annexe" room, hidden,

as it were, from my access. The

annexe room was in a dismal state, too. It lacked

the 24 hour air-conditioning that had sustained the main

archive for the past 40 years, and it was also

regularly flooded, ankle deep, as I often

witnessed in the monsoon. The

air in the annexe room was thick with the stench of mould, and the

occasional worker I saw there

would drink milk to obviate any sicknesses

caused by it. The humidity and moisture were surely steadily

destroying everything. The "annexe" desperately

needs climate control to save the many

hundreds of hours of speeches and other materials in the

room (for example, 24mm films by Syli-Cinema, stored

in rusting canisters). I transported all the music reels

from the annexe to the main archive.

Many were in very poor

condition. Though inadequately stored

and archived, there were only a handful of reels whose state had

become so deteriorated that they were unable to be preserved and

digitised.

A typical reel from the "annexe", with many metres

of tape at the beginning of the reel left un-wound and loose.

Such poor storage causes creases and wrinkles in the tape which affects

and distorts

its sound. Other reels in the main archive were never stored

in this fashion.

No climate control in the annexe caused mould to grow

on the reel covers and tapes. Many reels in the

annexe were in a very poor condition.

No climate control also allowed termites to eat the

covers and the reels.

Spot the

difference: the reels containing political speeches are on the right, while the reels of music

are on the left.

In

the annexe: there was so

much loose magnetic tape spilling over that reels were often

entwined

together.

It took many weeks to sift through the

unlabelled audio reels in the "annexe",

as each required comparison to

the 6,000 or so other songs already

archived, to avoid duplication. At

last, though, in early 2013, after

three major archival projects spanning six years, there were

only 50 or so audio reels left to archive... But, such was the

new-found enthusiasm for the project, RTG staff would locate

more! And so the project continued...

.

This occurred many times. It was impossible to know when the

work would all be done. But, in January 2013, satisfied that the

original audio reels of tape had been located, archived,

preserved and digitised, I called an end to the project. My

friend and my translator, Aly Badara

Fofana, celebrated together with a nice cold

bottle of Pastis.

For this 2012-2013 project, 5,210 songs from 827 audio reels were preserved, archived and digitised.

The total number of songs archived over the three Endangered Archive Programme projects (2008, 2009, 2012-2013) amounted to 9,410 songs from over 1,200 audio reels of 1/4" magnetic tape. This equates to over 55,000 minutes of Guinean music.

I presented the total collection of these archived songs to the RTG as 1,500 compact discs, and as digital audio files held within a 1tb external hard drive.

The "new" archive of reels from

all three Endangered Archve Programme projects: near completion

and stored in a climate controlled

space.

The entire collection of archived materials were relocated to a single climate-controlled room in the RTG (its photo above). With a week to go before I departed, publicity for the proiject peaked

and was being arranged by both the Ministry of Communication and the Ministry of Culture. A significant undertaking and commitment, given that for decades the Guinean public had known little of the existence of this incredible archive of their own music. From 1984, following Sékou Touré’s death, most of the music in the RTG archives was never broadcast. Given that archives are "sites of power", many a Guinean government had been wary of the potential of the music to inspire, to remind, and to reveal. Thus, for a generation, Guinea's national sound archive, held at the RTG in Boulbinet, Conkary, had been effectively silenced.

Through 6 years of preserving, digitising and archiving, I had

become attached to the collection. I

often thought, for example, of youngof them would

never have heard these recordings, and their loved ones,

the musicians themselves, had long passed away. Such was my motivation,

as it was a travesty that an entire generation of

Guineans had never heard their own music.

The project had thus become a personal mission, and I often

mused that the songs had been "asleep" for a long time and were

now "waking up".

The enormous scope of the sound archive's materials

- over 55,000 minutes of music - also reveals the

full extent through which the Guinean government, under Sékou

Touré, revitalised and asserted its cultural policy of authenticité.

For Guinea to progress, I believe it should embrace the old concept of "regard sur le passé", to borrow from one of the most famous recordings of the Sékou Touré era (Bembeya Jazz National, Syliphone SLP 10, 1968). To "look at the past" would embrace not only the music and politics of Guinea's pre-colonial era, as glorified widely by the traditional singer-historians, the griots, but also that of the post-colonial, namely the era of Sékou Touré and his successors. Guinea's contemporary politics, however, continue to present a reductionist dialectic of Malinké vs Fulbé. Though Sékou Touré was a Malinké, he loved the music of Farba Tela, a Fulbé, who performed for him regularly at the Presidential compound. That Farba Tela, the most popular of all Fulbé musicians, was never featured on a Syliphone release, yet was recorded on over 50 songs by the RTG (all digitised), is a sad illustration of the hypocrisies of the President and of his government's authenticité programme. I trust that the merit of the RTG sound archival projects is it that they reveal and present the many representations of Guinean culture for all to examine, to listen to, and to enjoy.

At the completion of the sound archive project, the Minister of Communication, Togba Kpoghomou, generously provided a grand lunch at Hotel le Rocher for RTG staff involved in the project. The Minister of Culture, Ahmed Tidiane Cissé, also arranged for a celebration at La Paillote, Guinea's premier venue for many an artist and orchestra since the early 1960s. Les Amazones de Guinee performed, as well as Keletigui et ses Tambourinis (featuring Linké Condé and Papa Kouyaté). The event was broadcast live on many radio stations, the Prime Minister telephoned in his congratulations, and the event was featured on the national television news that evening. It was a wonderful soirée and a fitting end to the project.

I acknowledge

and are grateful for the support of the

Endangered Archives Programme; the British Library; the Embassy

of the United Kingdom in Conakry; Sterns Music; the Bibliotheque

Nationale de Guineé; the Ministère de la

Communication; the

Ministère de la Culture (et des Arts et

Loisirs); the staff at Guinea's Sandervalia National

Museum; the archival staff at Radio Télévision Guinée; my

translators Prince E. A. J. Kenny, Allen Nyoka and Aly

Badara Fofana; musicians and friends; who all contributed to the

completion of the sound archive projects at the RTG. It

would not have been possible without their support, and I

dedicate the project to them and especially to

all Guinean musicians who

dedicated themselves to advance African music

and who performed in honour of their nation.

-

For further reading on these Endangered Archives Programme funded projects, see EAP 187: "Syliphone - an early African recording label" (2008) and EAP 327: "Guinea's Syliphone archives. See also The complete catalogue of RTG recordings.

Readers may also be interested in these publications:

- "Music for a revolution: The sound archives of Radio Télévision Guinée", in From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme, Maja Kominko (ed). Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2015, pp. 547-586.

- "Music for a coup - 'Armée Guinéenne'. An overview of Guinea's recent political turmoil", in the Australasian Review of African Studies. 2010, 31 (2), pp. 94-112.

All images and text copyright © Graeme Counsel